Can the California Buckeye be the mother of plants in a drying state?

By Etta Stewart and Ryan Suchomel

Contact: ebstewart@csuchico.edu and rwsuchomel@csuchico.edu

What does drought in California actually look like? We hear charged language like “desertification” all the time, so what is happening to our land? And what are scientists doing to prevent our state from becoming an enormous desert?

Desertification is a well observed phenomenon that describes the gradual shift in the climate of any plot of land from a productive ecosystem of plants, soil, and animals, towards a dry, barren desert where living things seldom survive. These kinds of changes are most prominently noticed in agriculture fields where people have not practiced sustainable land management. Things like overgrazing by livestock, lack of crop rotation, and misuse of water resources all contribute to desertification. Since California is one of the world’s leading exporters of produce with most of the land in the central valley being dedicated to agriculture, desertification risks are important for growers and scientists to assess and mitigate.

One of the ways we can help our land retain productivity (the rate at which living things like plants grow) and diversity (the number of different species living in an area) is through nurse plants. Nurse plants act as shields in tough environments such as the brutal California summers, providing shade and other favorable conditions for plants to grow in. We define these conditions provided by the nurse plants as the “soil microclimate.”

Many native plants in California not only survive the harsh conditions of the state’s climate, but they thrive in it. We decided to look at the microclimates underneath California Buckeye, a short tree with broad leaves that grows in canyon walls and along streams and rivers. Since the Buckeye is such a well-adapted plant to the climates most at risk for desertification, we hypothesized that it might have a nursing effect on the plants growing underneath it. Comparing the microclimates of Buckeyes with the trees nearest to them gives us an indication of how well the Buckeye performs as a nurse plant in its natural environments. This allows us to make an informed decision on the Buckeye as a “model organism” for mitigating desertification in mediterranean climates like Northern California.

Butte county is littered with streams, but as an agricultural community with cities and industry the streams are used very differently. Lower Bidwell Park is a city park that borders Big Chico Creek in the downtown of the city of Chico. Table Mountain Ecological Reserve is known for its wildflowers but is also home to over a dozen waterfalls and seasonally flowing creeks. The Reserve holds a profile of native species, untouched by urban development and only approached by weekend hikers. We wanted our study to be applicable to a range of locations, no matter how busy or pristine.

We picked 3 buckeye trees at Lower Bidwell Park (a site upset by human activities and local pollutants) and 3 at the Ecological Reserve (a site that is well protected from these disturbances) to sample for their “nursing” effect. To compare buckeye as a particularly generous plant, we also selected the nearest non-buckeye tree and sampled it the same way.

We sampled the conditions that these trees provided as well as the way that the vegetation underneath responded to the buckeyes’ help. We measured soil moisture, pH, depth of the blanket of dead leaves on the ground, how high the lowest branch was and the distance from the creek that the trees were growing around. We also used a rounded mirror called a densiometer to measure how much the tree leaves blocked out the sun which has an effect on keeping the microclimate cool but also can limit the amount of energy the plants under the canopy have access to. There was a big difference in canopy cover between the two types of trees with buckeyes having 83.3% canopy cover and the nearest trees having 62.4% canopy cover.

Next, we used a method called “point intercept” sampling to see who lived in these microclimates. There was diversity abound in these areas with different types of grasses, spring flowering forbs, shrubs, water loving sedges and tangled vines. We surveyed the percentage of the ground that is covered by each category to see the relative abundance and diversity of plant life underneath these trees.

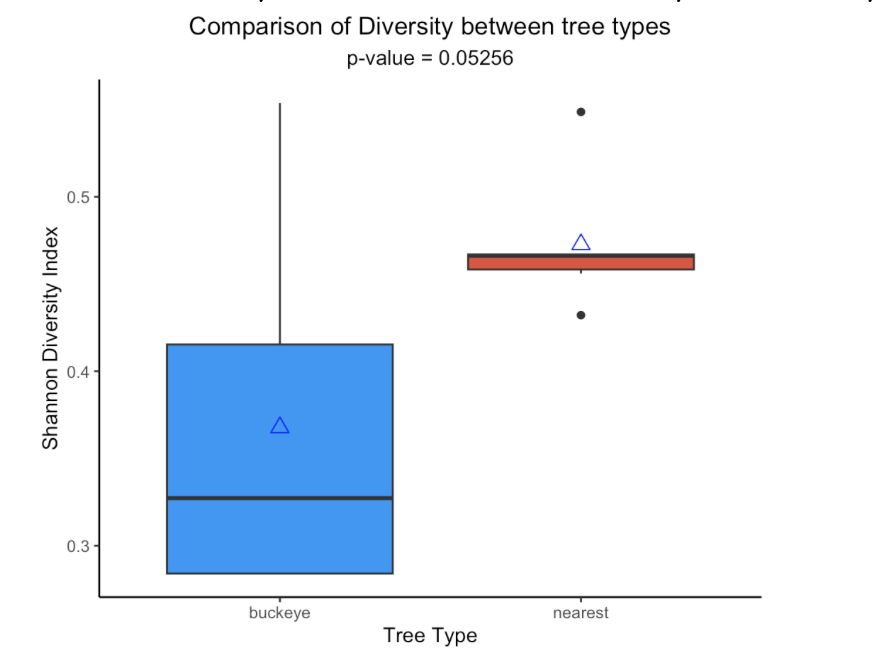

From our measurements of diversity, we found that the nearest trees actually had a higher mean diversity (the triangle on our graph) relative to the Buckeye. The Buckeyes also had a much wider range of diversities in the sites that we sampled. This appears to indicate that the Buckeye might provide a less welcoming habitat for other species. This might be due to several factors specific to the Buckeye, such as its higher canopy cover or even allelopathic properties (a defense strategy where plants send toxins into the soil around them). However, it’s important to note that our sample size for our trees was very limited, as well as our ability to accurately ID plants.